Quibble, 27. Consensus

Among the bustling Adroit, Quibble learns the disturbing truth about Citation's death. Unity brings her a nightmare.

27. Consensus @Quibble

The cart rattled into the Adroit consensus two hours past noon the next day, the third labor in the heat. Nish asked a passing Adroit where to deliver our load of wool. Following his directions, she stopped the cart at a low wooden shed. Two Adroit came out to meet us. Nish sent one of them off to fetch Bibliography. The other, Note, began the unloading with our help. His name, he told me, was an abbreviation of Annotation.

The other Adroit returned, bringing Graph. He wasn’t at all what I expected. Short and stocky, with a blacksmith’s muscles, he was much older than Nish though not as old as Cate. He had hazel eyes, blond hair going white at the temples, a close-cropped beard. He wore a broad leather apron, and some soot was settled in the lines of his forehead. I would learn he worked in his smithy even on Sing. Though he looked odd next to Nish and I couldn’t imagine the two of them ever having been adroitnesses, he was unmistakably alert and lively, as adroit as One ever becomes. He greeted us both with a wide grin.

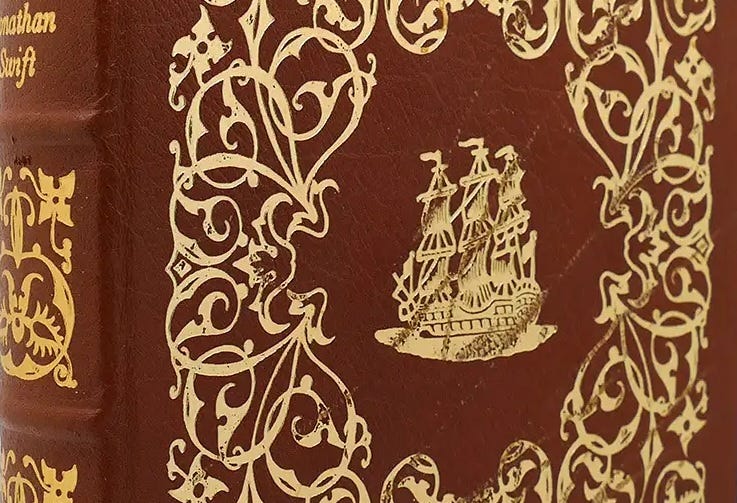

I fetched a book from the cart’s spring seat. It was a hardback volume, bound in leather with gilt-edged pages. Its cover bore an engraving of a sailing ship, also gilt, sadly scored from someone’s reckless handling. As we’d set out the previous morning, Cate gave the book up with clear reluctance. Inside, its title page read: Gulliver’s Travels, A Tale of a Tub, The Battle of the Books, The Bickerstaff Papers, The Drapier’s Letters, A Modest Proposal. I’d perused the book on the way. Now, I handed it to Graph just as reluctantly as Cate had to me. “A gift from the Dazed library,” I told him.

“Lovely,” Graph said, flipping through the book. “What’s the Tale of a Tub?”

“The strangest satire!” I said. “There are three brothers, and they have to share a coat their father gave them, except—”

“Later,” Nish remonstrated. “Help me unload, Quill.”

“Nish, leave it to the Notes,” Graph said. “It’s their job.”

“Notes?” I asked, confused.

“Annotation and Footnote – believe me, you’re not the first. Footnote, make sure that horse gets fed! Come on, I’ll give you two the penny tour.”

Graph was almost too absorbed by the book to show us around the consensus. “I never read this scrivener as One,” he remarked.

“Read it and you’ll see why,” I said. “He was a priest. A censor writing heresy!”

Nish hung somewhat behind us, and with a skance over my shoulder I saw she was feeling glum. I took her hand and brought her to me, without a word insisting we walk side by side. She brightened at my touch, though she still said nothing.

Set in a flat trough between two hills, the Adroit consensus was a series of mostly stone cottages built in concentric rings around a large empty circle. The largest cottages faced the circle, which was paved in cobblestones. As Ones did in the spirals Within, the Adroit called the center of their consensus the Axle. Between each ring of cottages ran a circular street, also paved with cobbles. Here and there stood wooden sheds, granaries, warehouses, and outbuildings, thatched with straw like the cottages.

There was noise everywhere. The Adroit were industrious, apparently only happy if they were making a racket. The place swarmed with people going to and fro. All their faces were uplifted, and almost without fail their eyes met mine.

In a field between the outermost ring and the foot of the hill situated northeast of the consensus, we saw four Adroit surveying and staking out ground.

“Another ring?” I asked.

Graph beamed. “No, a factory! We’ll have a Bessemer furnace, an assembly line, large-scale manufacture. We’ll be able to make anything, absolutely anything!”

“Well,” Nish carped, “what do you need?”

“To electrify the consensus, who knows? But we’ll begin with a telegraph system going up the mountain, so all your Dazed can find out what’s happening down here.”

“I’m not sure that’s a good idea,” I said, noting Nish’s frown. “Dazed need quiet, freedom from distraction. They live monastically because it suits them.”

“Oh, yes, I know that,” Graph replied, waving his hand as if brushing objections aside. “What they really need is a good shaking-up, though. And anyway, if indeed the Ones are coming Without, what with an excelsior and all—”

I stopped him short with a hand on his arm and a stern glare. “Is that the song going around this consensus?” I said.

He blinked at me, surprised.

“If it is, nip it in the bud,” Nish said. “There is no exodus of Ones. Quibble isn’t anybody’s messiah. This isn’t the first we’ve heard of it, but I’m telling you, Graph, and mark I mean it well, it had better be the last. She’s in bad enough trouble already.”

That reprimand sobered Graph, and he concluded the tour with less effusiveness and more haste. We retrieved our packs from the cart. Graph showed us into an empty cottage in the second ring of the consensus, which he said had been vacated by his new adroitness, Concordance, for our lodging. To our dismay, the cottage’s windows faced cottages to the left and right of it – little light. Nish gave me a sour skance, and we were about to protest when Graph opened the door onto the second room, a bedroom. It was flooded with sunlight. Framed in the roof directly over the bed was a large eight-paned skylight. Nish smiled, barely holding in her delight.

“Tell Cord we thank her,” she said to Graph. “How is she, anyway?”

He rolled his eyes and harrumphed: “A handful!” He invited us to have supper with them, and then he was off to his smithy.

Sharing a skance, we tossed our packs to the floor and tumbled onto the bed.

“Acorn!” Graph blurted, throwing back his head in mirth.

“Well, not just acorn,” I said, imagining he missed the point and annoyed too at having my recitation interrupted. “First Lysander calls her a dwarf, then a weed, then a bead. It all builds up to acorn. And this is the girl he really loves.”

“Don’t parse scripture for him,” Cord told me, wryly smirking as her adroitness went on laughing. “Just let him have acorn.”

Cord offered to refill Nish’s mug and was politely refused. Nish ate sparingly; her glumness had returned. I leaned over and whispered, “What’s the matter?”

“Where are the Zeros?” she whispered back.

“Being discreet.” At least, I thought, I hope that’s the case.

Cord appeared to have noticed our exchange, but she said nothing. Rising, she began to clear dishes from the table. When Nish started to rise too, Cord showed her an open palm: You’re a guest. After helping Cord with clearing away, Graph went to the mantelpiece, took down a short-stemmed pipe, knocked out its ashes against the hearthstone, filled it with a green-and-orange herb from a cedar box, and lit it with a small ember he picked from the fire with tongs. Taking his chair again, he drew deeply on the pipe, then offered it to me. I shook my head. Nish accepted it, dragging in smoke as deeply as Graph had. At once she coughed out a cloud of smoke; it hung around her head as she wheezed. Getting her breath at last, she sputtered, “Kindness!” She gave the pipe to me with a scolding skance at Graph. He was laughing quietly. I took the gentlest breath in I could, held it, breathed it out. I took another. The smoke burned in my lungs, but I didn’t cough. My head buzzed a bit. Cord sat down, and I passed the pipe to her.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Not sure,” Graph said. “Got it from an Isleh-ri. She called it qeht-li-qah – that’s ‘companion with the blood.’ Or ‘with water,’ or ‘with the sea’ – I don’t know! The Far word qah confuses me. Qeht-li-qah is like an orb. Their shamans dream with it.”

Nish waved fingers in front of her face. “It’s dreamy, sure enough,” she droned.

“Ah,” said Cord, handing the pipe to her. “Have a little more, and go easy.”

“Speaking of—” Graph skanced Nish as she took a suspicious puff. “—let me set your mind at ease about that song. I had a chat with the Notes, dropped a hint.”

Nish stared at him. “You dropped a hint?”

“That’s how it is here,” Graph went on after a sigh. “A hint is all they had to start with, and that’s all it takes. Every Adroit in the consensus knows two things by now: there are no Ones coming Without, and shut the hell up about the excelsior. I’m sorry they didn’t know already. Enthusiasm got the better of me.”

“It’s all right,” I said. “We’d better watch our words, too.”

No forgiveness was forthcoming from Nish. I eyed her with as much seriousness as I could muster under the effect of the qeht-li-qah, which made me want to giggle.

“Quill,” said Graph, “what are you going to do?”

All eyes fell at once on me, and I found myself speechless.

“Nothing she doesn’t want to,” Nish put in for me.

“If you don’t mind, Nish, I’d like to hear it from her. Quill, that silence, Aladfar, gave me to understand we’re taking a risk harboring you.” Graph’s eyes flitted briefly towards Nish, then back to me. “That’s by the by – life is risk. I just want to know your plans, what we’re risking our necks for.”

“I don’t have any plans,” I began. Then, to clarify: “No plans as far as excellence goes, anyway. I just want to find out what happened to my mother. If she’s alive, where is she? I told Alnasl that when I came Without, but he’s kept mum about it ever since. Then all this nonsense came up. Bit by bit, I’m getting a picture I’m the queen in a chess game Vega’s playing. How can I use that?”

Graph gave Cord a look as if cuing her, and she said, “Quill, maybe it’s the furthest thing from your mind, but I suggest you make some plans about your excellence. Vega is crafty. You can be sure she’s making plans. If you don’t, you’ll just end up going along with hers. Like Citation did.”

There was a long silence around the table.

“Did you know him?” I asked Cord.

“Graph did. I was already here.”

“He was my first adroitness,” Graph said. “Not like you and Nish, but we were close. Cite was like a son to me. That’s two the Zeros took.”

He rose. With a sudden curse – “Damn their edict, damn their eyes!” – he knelt at the hearth with his back to us. His shoulders shook as he knocked ashes out of the pipe. My eyes went to Nish. She skanced me: I didn’t know.

“Cate said he was brave,” I ventured, unsure of the wisdom of speaking. “I guess he thought it was a brave thing to do, giving kindness to the Ones. The lady of kindness may have really believed the dreamless orb would turn blue, I don’t know. Cate’s right, though. She should’ve been aware she was risking Cite. The first excelsior made the orb that rectified him kind by giving up his transcendence. It costs at least that much.”

Graph grew still, turned to me, and wiped his eyes with his fingers. “You mean,” he said, “you don’t know?”

Surprised, I stared back at him. “Know what?”

“Cate gave you the wrong end of the stick,” Graph told me. “Cite knew he’d burn. And he was successful. He died in the hub fourteen years ago.”

When I gave Graph only an uncomprehending look, he sat again at the table, leaned towards me, and fixed me with a gaze. “Think back. How old were you then?”

“I’m seventeen now. So I guess I would’ve been three.”

“And where were you?”

“Um, let me see. Fourteen years is twenty-eight Fears. I was with my consensus seventeen Fears – no, it was eighteen, it’s just that Quiddity vanished at my next-to-last Fear. Before that, I was in the Large Spiral ten Fears. That makes twenty-eight.”

“And what happened during your first Fear in the Large Spiral?”

I blinked in surprise at Graph’s intuition. “I saw shadows.”

“You didn’t look at the orb?” said Cord.

“Of course I looked! But it was dreamless. How could it trance me?”

“Did the other Ones look away?” Cord pressed. “Or ever mention the shadows?”

“Kindness, no! I told One about them, but he hadn’t a clue. When the Ones filed out of the Depth of Night, Rasalased took me out of line, and the One called me heretic. The lady had caught me looking away, you see. I told her about the shadows. She—”

“She kept it secret from Unity,” Graph said. “Cite gave his life so that you could see shadows Within, Quill. It had nothing to do with turning orbs blue or making Ones kind. He was creating another excelsior, stronger than himself.”

Now I gaped. “That was Vega’s plan? How did she know it would work?”

“Tell me, Quill,” said Cord, “how were you born?”

My mind had let go of nothing. “Wakeful. Quiddity said it made me precocious.”

“And how was she born? Did she have a Passage, dreaming?”

“No. She was born the same way.”

“Seventh son of a seventh son!” Nish interjected, slapping her hand hard on the table. We all looked at her. She went on: “It’s a scripture in the folklore of the Ancient. The seventh son of a seventh son acquires supernatural powers. A seventh daughter’s seventh daughter becomes an oracle, a prophetess.”

“I doubt Vega believes folklore,” Graph observed. “But maybe there’s benefit in being born wakeful, without glasses and orbs flashing in your eyes.”

All four of us sat back in our chairs at once. It struck me as funny, like something One Within would do, like singing because other Ones sang. Unlike with the Zeros the night before, Nish and I harmonized with Graph and Cord. There was no dissonance between us. We had consensus. We were plainspoken with each other, open with our thoughts. Each of us understood the others quite well. A pang of regret for coming Without stabbed at me. I hadn’t known I missed this.

“So,” I said to Graph, “Cite sacrificed himself to fulfill the promise Meissa made, and my birth brought it about. I’m amazed you don’t hate me.”

“Why should I? It’s not your fault.” Rising again, Graph said, “Leave it,” and we all agreed. “Who’s up for a second pipe?” To this we agreed, too. “Quill, I want the rest of that romp in the woods. Robin’s turned everything nicely upside-down.” Graph grinned. “How far is he going to take it?”

I dreamed that night I was Within.

Above me yawned a tarry-not wider than any in waking life. Through it deluged Without. I looked down to see myself garbed in the gray cloak of a Zero protégé. Light rushed down the cloak’s folds, making them a silken waterfall.

Around me danced Ones, nude and rapturous. Heads thrust back, eyes wide, the Ones gazed up in wonder at Without. They didn’t fear it. They hummed melodically.

“For to see the face,” I sang to them, “is to know the person!”

“For to see,” the Ones chorused after me, “is to know!”

I called: “For to know is to love!”

They echoed me.

I repeated the whole refrain, and the Ones sang with me in full choir, according with me in the song. All were One, and I was One with them – we were a consensus. Our voices wove, contrapuntal, in a haunting music.

“You dream!” I sang, and they answered: “We dream!”

“While you look at dreams—”

“While we look at dreams—”

“—the world Without wends along!”

At once the light of Without pouring through the tarry-not shone red, a crimson like blood. The Ones shrieked in terror, hiding their eyes with their hands, and fled into the darkness of the spiral. I was left alone. Below me, in the bowels of Earth itself, there was a grumbling, a massive discord like splitting rocks. A voice boomed around me, as if coming from everywhere. It spoke in decree: “There must be control.”

Though alone and frightened, I answered, “There must be life!”

“Recite the confessions,” the voice commanded.

From the dark recesses of the spiral came the voices of Ones, obeying, chanting without tone or lilt: “All are One.”

“No!” I cried. “Each of you is a different One!”

“We are a consensus.”

“You’re slaves!”

“Before Unity, which is the sacred heart—”

“Damn Unity!”

“—of the dream, censoriousness is perfecting. We censor ourselves—”

“You kill yourselves!”

“—that we may avert our souls from the impurities of the seen—”

“The seen is pure! You annihilate your souls!”

“—wherein lies Without.”

With that last phrase, suddenly I was in the dream of the crimson sun. It did not seek to rectify me. The sun throbbed before me, consuming me, but this time it was not painless. Hot spasms raced through my body. I tried to break free of the pulsating orb – pain, touch, a thing – but no other colors appeared, no swirling kaleidoscope fought back the crimson dream. All was sun. It gave all the light I could see, held all the power in this hell. I fought now even to take a full, deep breath.

“You can’t have it!” I screamed, delirious, not knowing what I refused to give up.

“I don’t need to take it, Quibble,” declared Unity. “I only need to touch it. I have touched it already. It is mine!”

I shut my eyes fast, breathlessly convulsing. Then I woke to violent shaking. Nish was kneeling over me on the bed, hands clasping me by my shoulders. A gibbous moon shone behind her in the skylight. “Quibble!” she yelled right in my face.

“I’m here! I’m awake!”

I gripped the sheets, gulping for air. In, out. Slowly, deeply. In, out.

Nish let me go and backed away, and then all I saw was the moon.

In, out.

When at last I had control and sat up, I saw Nish hunched against the wall on the far side of the room. Her arms were draped across her knees, her head down. I heard a faint sound of sobbing. I spoke to her as gently as I could.

“I’m sorry. It was a nightmare.”

She looked up. “A nightmare? You were screaming to wake the rectified!”

Mixed with Nish’s fear was accusation. Without intending it, I echoed her tone: “Why’d you shout in my face, Nish? I woke up. Didn’t you see me open my eyes?”

“Your eyes were open the whole time!”

“No, they weren’t! I was dreaming.”

“They were, they were!” Nish dropped her head again and burst into fresh tears. “Your eyes were open,” she blubbered.

I got out of bed, found my shift, put it on. Then I went to her, though at a loss for the right thing to do. I leaned against the wall, inched down to sit next to her, and put an arm across her shoulders. She fell against me.

It was the third time I’d held her as she cried. The second was in the forest, when the lady of control said I was as likely to become a demon, an excelsior of utter control, as to become the angel the lady of kindness thought I was. The first was the second time we practiced our adroitness. It overwhelmed Nish. Between sobs, bit by bit, she told me the story of her grief: her adroitness with Graph, the joy their son Index brought to her and all the Dazed, her terror when he was discovered by prying Zeros, the ill-conceived lie the Zeros didn’t really believe, the lord of control Alioth’s demand to satisfy edict, how Alioth blinded Index with a control and popped him to a vale on the far side of the mountain and left him as prey for the packs of wolves prowling there, and how, after all that, Graph abandoned her to go live with the Adroit. It was a hard story to tell.

Nish was not yet thirty years old – she’d lost count of her Fears young, she said – but already she had been through pain and hardship enough for a lifetime. Now I was another burden to her, another grief. Selfishly, I didn’t want to send her away. Of course not, I thought, you love her.

No, it wasn’t really that. I was a coward. I knew she’d have to leave me, sooner or later, but I didn’t want to be the one to tell her to go.

She sniffled and wiped her nose on the sleeve of my shift. Then she laughed a bit, sobbed again. “This tattered old thing. I’ll bet Cord has a new one you can have.”

It was the shift I came Without in. “It suits me,” I said.

“Quibble?” she said, so lightly I almost couldn’t hear her.

“Yes, adroitness?”

“What’s happening to you?”

< Previous chapter | Index | Glossary | Appendix | Next chapter >

rem

Questions about process? Thoughts on chapter-reflection pairings? Feelings about the developing love story in the novel?

Part 5, read: Call for Feedback

In the upcoming weeks, in a new multi-part reflection series titled “Infinite Lock-In,” I’ll dive deeper into concerns and criticisms about the Singularity. Moving past my objections to Ray Kurzweil’s utopia, I’ll start to engage with the ideas of a futurist and tech pioneer I admire, Jaron Lanier. Reflections are only for paying subscribers, so if you …