Opening Organically

A reflection on the opening of Octavia Butler's Dawn with false-start excerpts from early drafts of Quibble.

Breaking news! The Museum of Americana, a wonderful literary journal, is bringing out my song “My Sweet Ruth” in its American Songbook series. I wrote it in a dark time, unemployed after my first year of teaching, fearful it meant my teaching career was on the skids, and being pulled this way and that by long-unrequited love (I had a talent for that once). So it’s plaintive.

I made this recording at home — yes, I’m playing all the instruments — in 2020. My profuse thanks to music editor Cal Freeman, executive editor Justin Hamm for telling me the journal was seeking songs, and production manager Jenn Hendricks for taking pains to get things just so.

I debated what to write in reflection on chapter 6, “Without,” and the first part of the novel, “if then.” This is the only part which takes place entirely Within, and with its conclusion, dystopia is doubtless coming into focus as a genre in which the novel is participating — but I think it’s too early to reflect on dystopia, despite the many things I want to say. Instead, I’m following up on last week’s reflection, which I ended with the first point-of-view scene from the novel’s junked first version. Let’s take a closer look at false starts. But before getting to that, let me paint in some background, so you can see what sort of preparation and mindset I had early on.

I began writing Quibble the year after finishing an M.F.A. in poetry at the University of Maryland. My program of study was very light on fiction: I took two surveys of 18th and 20th-century literature and one Form and Theory in Fiction course which looked particularly at first-person narration. The latter course, taught by the novelist Maud Casey, was just brilliant. I recall especially loving our discussions of So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell and Versailles by Kathryn Davis. I wanted a storyteller’s opinion on the narrative-heavy poetry I was writing then, so I tried to rope Maud into my thesis committee. No joy: the department frowned on cross-pollination between the program’s poetry and fiction sides. So I read fiction at Maryland but I learned next to nothing about writing it. I never took a fiction workshop. With a head full of poetry and ideas about writing that, predictably I had quite the bumpy time of getting started on a novel.

It was a counterintuitive thing even to attempt. I remember at least a couple of people expressing doubts about what I was doing. Why write fiction at all, even if I was still writing poetry? Logically, shouldn’t I write only poetry? Shouldn’t I do all I could to get poems published, rework my thesis into a solid first collection, land a residency or a fellowship or admission to a Ph.D. program? In short, why wasn’t I trying to get an academia-housed writing career underway, like some other folks I’d studied with?

Having seen how much research inundated the Ph.D. students with whom I’d shared office space, I decided I wanted no part of it, at least not yet. I wasn’t wholly burnt-out on reading research. Right out of the M.F.A., I took a communications job with the university’s college of education in which I interpreted plenty of research for the lay public. But I felt my poetry was growing too informed by critical theory and it needed a breather from all that. I continued to write and publish poems. I applied for some residencies and fellowships (again no joy). I set about reworking my thesis into a book. Kathryn Stripling Byer, a fellow Southern poet I’d started reading in grad school and then befriended online, took a shine to my poetry and endorsed my manuscript with her editors at Louisiana State University Press, but nothing came of it. Meanwhile, though, I also got hold of an idea for a novel — or it got hold of me. So I threw myself back into my first loves as a reader and a writer, which had been sci-fi and fantasy.

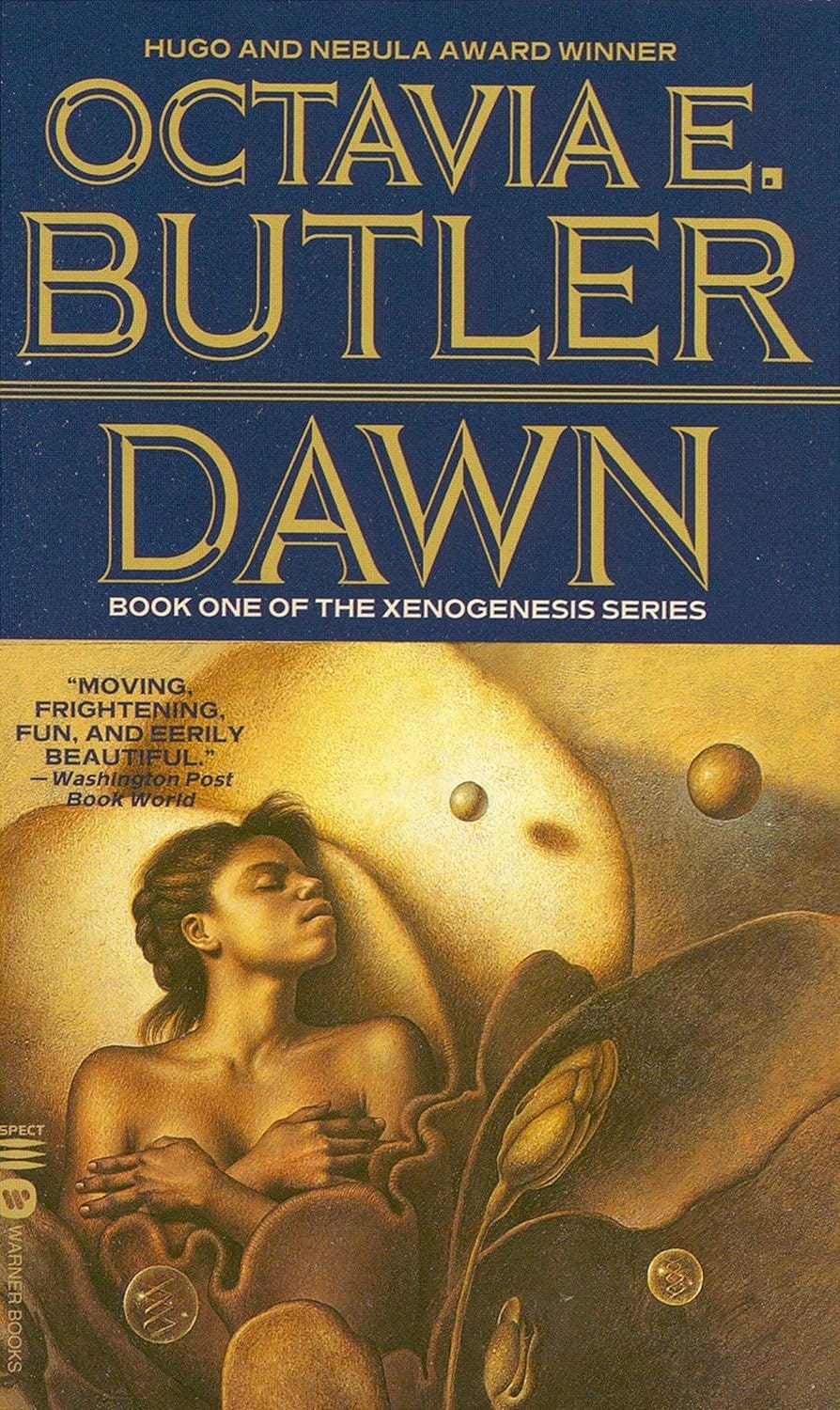

With this redirection came a lot of reading. I reacquainted myself with SF/F and dug deeper into the works of my polestar, Ursula K. Le Guin. I read and reread and reread yet again both A Wizard of Earthsea and The Left Hand of Darkness, considering what I wanted to emulate. Since my novel was about transhumanism, I read Ray Kurzweil and Jaron Lanier to get both optimistic and pessimistic perspectives on it. And I read so much more — you’ll hear plenty about it in my forthcoming reflections! But one of the most head-turning things I read wasn’t about transhumanism. It was far afield, in fact, from anything I wanted to write about. It was a highly original sci-fi novel about first contact with extraterrestrials: Octavia Butler’s Dawn.

Butler is better known these days for her Parable books (post-apocalyptic / dystopian sci-fi about religion) and Kindred, a time travel story about the legacy — and, for the novel’s protagonist, the all-too-present reality — of American slavery. But two things drew me to Dawn as a source of inspiration for Quibble. Butler’s heroine, Lilith Iyapo, is a beautifully conflicted character, torn between an irrecoverable past and a present situation demanding resourcefulness and ingenuity, torn as well between revulsion at what her alien Oankali captors — or are they her saviors? — ask of her, what seems by default to be the right thing to do instead, and what intrigues and thrills her. I wanted to write Quibble as such a conflicted character, as I felt she must be, offered a chance to acquire surreal powers she knows she’s really not mature enough to handle wisely. Also, for the first half of Dawn, Lilith is alone among the Oankali. Butler uses this to explore feelings of alienation, fascination, and helplessness. Quibble too experiences these feelings when she first leaves Within, the subterranean world of Ones ruled by Unity, and comes Without. There, Quibble isn’t living among aliens, but the reality into which she’s stepped is so otherworldly and the people there are so strange to her that she might as well be.

To see how pivotal Dawn would become to the writing of Quibble, first let’s look at my novel’s opening scene in a draft I called “2nd edited toward 3rd” (spring 2018). I had by this point long abandoned the junked version I showed you previously, written a first draft to completion on manual typewriters — first a Smith Corona Super Sterling on which I’d written my M.F.A. thesis, then an Olympia SM8, a much better machine — and revised it into a second draft using Scrivener (software I heartily recommend for working on long manuscripts). Now, in the transitional “2nd edited toward 3rd” draft, knowing what I’d written was not yet what I wanted it to be, I was exploring possible ways forward. Here’s the opening scene:

Alerted to her approach by sensors, the nanos — agile, delicately quick — fled before Quibble, dashing along the smooth floor of the Alabaster Chamber and scurrying around the feet of the silent, prayerful Ones. Quibble hurried, paying them no heed. Though it would not take her directly to the door at the chamber’s far end, she took the easiest route: a diagonal line through the ranks and files of Ones, who stood mutely in place, their hands raised in benediction, like reverent checkers on a vast checkerboard.

Quibble skanced the Ones to her left as she walked past.

How fortunate they were, how placid and untroubled in their reverie, how gentle. Acolytes, devotees, their faces uplifted, eyes wide and rapturously adazzle, all gazes transfixed. They took no notice of Quibble or the isos — the tallest nearly shoulder-high — moving diligently among them. Not so much as a skance was spared for anything but the object of their devotion: a giant, oval glass hanging in the air, held aloft by nothing visible. It shone dully blue. Was it their faith that made it float like that?

Quibble knew better than to look at it herself.

I’ll go to Indication first.

The oldest and wisest Dazed, Cate could answer any question. The Zero had been no help. Whether unable to comprehend her question or unwilling to answer it, Osiris gave her only an absent stare, then left her alone with her reflections. One moment he was there, the next not. So typical of a Zero to vanish like that.

Somehow stranger than what she had seen and experienced was the lack of a word for how she felt about it. Abstractions danced through Quibble’s mind: clarity, recognition, insight. None of them seemed to fit. In one vertiginous instant, something became real which had been unreal, unfathomable. In substance, nothing changed; in perception, everything did. Something already there but hidden revealed itself with a simplicity that shocked her. Revelation, realization — better words, but still inadequate.

Cate could explain it. If not Cate, perhaps Nish. Definition said surprising things.

Quibble sped up, anxious to be aboveground. Gaining the upper left corner of the phalanx of Ones, she pivoted right, toward the night-door. The nanos and isos were gone, tucked into their burrows or nests — Quibble had never learned where they went when their labor was done. With a jolt, she realized the chamber was quickly darkening.

She chanced a brief glance at the glowing glass, almost overhead. Its illumination was fading. Soon the Alabaster Chamber would descend into pitch black, the subterranean night in which Ones woke from their dreams and spoke to each other and explored their universe of touch. Quibble had to reach the door before night fell. She broke into a run.

The light was almost gone when she pressed her hand against the door’s stonework. There was no seam, no sill. Only a difference in color — the door was jet black, the surrounding wall the pale, striated yellow of sandstone — hinted at an exit. Quibble leaned on the door a moment, catching her breath. Then she turned and faced the Ones, curious to see their ritual’s last moments.

Darkness had spread all through the chamber, save an arc of deep blue light bathing the naked bodies in the rows nearest the glass. The Ones’ hands were still raised, worshipful. All of their faces were streaked with tears. Farther back, enveloped in shadow, a thousand eyes echoed a faint blue sheen.

No, Quibble decided, suddenly terrified, I can’t look at this.

Touching the door behind her, she whispered the word Bastet had taught her, the word of release. The word was a heresy in the language of Ones.

“End.”

The crying eyes blinked into nothingness.

A few things I like about this:

There’s an immediate sense of action. Robots — “nanos” — react to Quibble’s presence, zipping away from her. Quibble herself hurries toward a destination.

The world Within, among Ones, is being built quickly, and though we see it in rich visual detail — “the ranks and files of Ones, who stood mutely in place, their hands raised in benediction, like reverent checkers on a vast checkerboard” — all the same there’s a lot of mystery. Why do Ones stand in formation? Why do they worship the glass? Why, as they worship, do they cry? Who are they?

The story is beginning in medias res, “in the middle of things.” Already something important has happened, and Quibble is reflecting on it. So the plot is underway and there’s urgency for Quibble about getting her questions answered.

Things I dislike:

Despite the sense of action, nothing actually happens. Quibble runs to a door — that’s it. I neglected even to tell the reader why she’s racing against descending darkness to reach this door. Here’s the explanation: It’s a night-door which will teleport her Without. If she doesn’t reach it before the glass’s light dies and night falls Within, she won’t find it, so she’ll be trapped Within. When the glass lights again, it will trance her, make her dream, and then she may become One again — and never escape. Quibble is in fact racing to stay free. But is that made clear to the reader? No. The reader will only figure this out much later. So maybe there’s action in this scene, but what’s at stake in it is anyone’s guess.

There’s too much mystery about why this scene, set amid Ones Within, comes at the start of the story. Yes, it shows us the Ones and implies they’re important, but it doesn’t say how. It tells us nothing about Quibble’s relationship to the Ones, certainly not that she once was One. Again, it only sets up later disclosures for the reader: “Here’s some information for you to hold onto for later. I’m not telling you why it’s important, just that somehow it is. So be ready for a revelation to spring on you anytime about why you need to know this.” That’s not a welcoming way to treat the reader at a story’s outset.

The reader has no idea what the important event on which Quibble reflects is. In fact, the scene might confuse the reader: “Was it their faith that made it float like that? Quibble knew better than to look at it herself. I’ll go to Indication first. The oldest and wisest Dazed, Cate could answer any question.” With paragraph breaks removed, do you see the problem? The question Quibble intends to ask Cate is not “Do Ones’ faith make glasses float Within?” — that’s just a casual aside as she’s thinking about an even more perplexing matter which the scene leaves a complete mystery, except for mentioning a Zero was present. It’s not a felicitous mystery, enticing the reader to learn more. It’s just a hole in the story that’s got to be filled later — with flashback chapters, after Quibble palavers with Cate and Nish.

Her reflection on this unknown event — “Abstractions danced through Quibble’s mind: clarity, recognition, insight. None of them seemed to fit. In one vertiginous instant, something became real which had been unreal, unfathomable.” — might be interesting if we knew her better, if we had a firm grasp on her character, if we understood how she thinks and what impressions “real” and “unreal” things make on her. But this is the opening scene: we know nothing about her yet!

For every positive, then, there’s a corresponding negative, a drawback. But the novel’s opening would get even worse before it got better.