This may come as a surprise: I love Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books.

Yes, I know, I write nothing like Pratchett. My characters crack jokes, of course, and Quibble is fond of literary witticisms, but her story’s never a comedy or a farce or even a satire, though I found my way to writing it by first trying to write satire. None of the jokes in Quibble are extended: they’re here and gone, like a crack of lightning. So, of all the sources I could discuss, why am I starting with Pratchett, with Discworld?

Well, first, let’s set the record straight about the Discworld books: they’re serious. Yes, they’re absurd and hilarious. Yes, Pratchett’s humor ranges from the ironic and droll to the slapstick and scatological. Yes, it’s obvious from the moment you see a cosmic turtle with four elephants on its back holding up a flat world — an image Pratchett evokes in some new way in each book’s opening — that none of this is serious. But no, it’s all serious. It’s very serious. The Discworld is a carnival-mirror image of our own, and Pratchett uses it to explore his ideas about the best and worst in people.

For instance, the Watch novels, which spoof hard-boiled detective stories as they follow the adventures of the “copper” Sam Vimes, are flush with ideas about politics and justice. The Witch novels explore the difficulties of human relationships as they depict the everyday spats in an oddball coven of witches (“the maiden, the mother, and the other one”). The Death series, of course, is an extended meditation on mortality. And as for Rincewind, well, he’s Rincewind: he goes everywhere, meets everyone, and learns something about everything — but for all his shenanigans and tomfoolery, what he learns at the end of each story is often quite a heavy “something.”

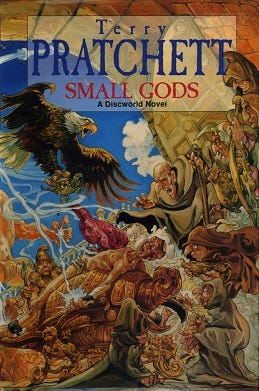

But my favorite Discworld book is the stand-alone novel Small Gods. It’s about religion and philosophy. In particular, it’s about how religions begin, flourish, decline, decay, and — just maybe — revive. I think Pratchett’s point boils down to this:

Every religion is born in heresy, and every religion dies in orthodoxy.

Brutha, the hero of Small Gods, is a heretic facing off against the machinations, lies, and political intrigues of a theocratic orthodoxy which — uncomfortably for many believers, I’m sure — all too closely resembles what prevailed during a certain era in Christianity, namely the rule and terror of the Inquisition. Vorbis, Brutha’s mentor-cum-burden-cum-torturer, represents the pitfalls of orthodoxy, especially how it can become a breeding ground for selfishness, hypocrisy, doublethink, and outright evil.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Singular Dream to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.